The Law of Surprise | The Central Fairy Tale of the Witcher Saga

The Witcher’s plot is based on a universally known fairy tale, where a monster (or a wizard) saves someone’s life and asks for something in return. The Law of Surprise. In its frustration and desperation, Ciri’s offer to Avallac’h comes off as a perversion of the way Ciri first chooses Geralt.

‘Or you, perhaps?’ she yelled. ‘If you want I’ll give myself to you! Well? Won’t you sacrifice yourself? I mean, they say I’ve got Lara’s eyes!’

A merchant was traveling through a dense, dark forest; he wandered for a long time and in the darkness of the night got stuck in a swamp without salvation. Saddened, he began to despair, when suddenly an evil spirit appeared to him in human form. ‘Do not be sad, man!’ he said to the merchant -- ‘I will pull you out of the mud and show you the way home, but on condition that what you have at home and do not know about, will become my property.’

– Lucjan Siemieński, Polish, Russian and Lithuanian Tales and Legends

The Witcher’s plot is based on a universally known fairy tale, where a monster (or a wizard) saves someone’s life and asks for something in return: ‘You’ll give me something you’ll find at home but do not expect.’

‘On this is based the tale A Question of Price (Kwestia ceny) and The Sword of Destiny and at the end of the day, the entire saga.’

– A. Sapkowski, Interview

It was usually payment for a favour from an evil spirit, a devil. In the Cycle, a witcher (a menacing monster killer) enacts the fairy tale first, through the Law of Surprise. Later, a wizard does; developing an imitation. In such fairy tales, an oath and hope that the oath will be kept (‘Destiny is hope.’) underpin exchanges by which people’s fates are forged.

’Why should anyone want such an oath? You know the answer, Urcheon of Erlenwald. It creates a powerful, indissoluble tie of destiny between the person demanding the oath and its object.’

– Geralt, A Question of Price

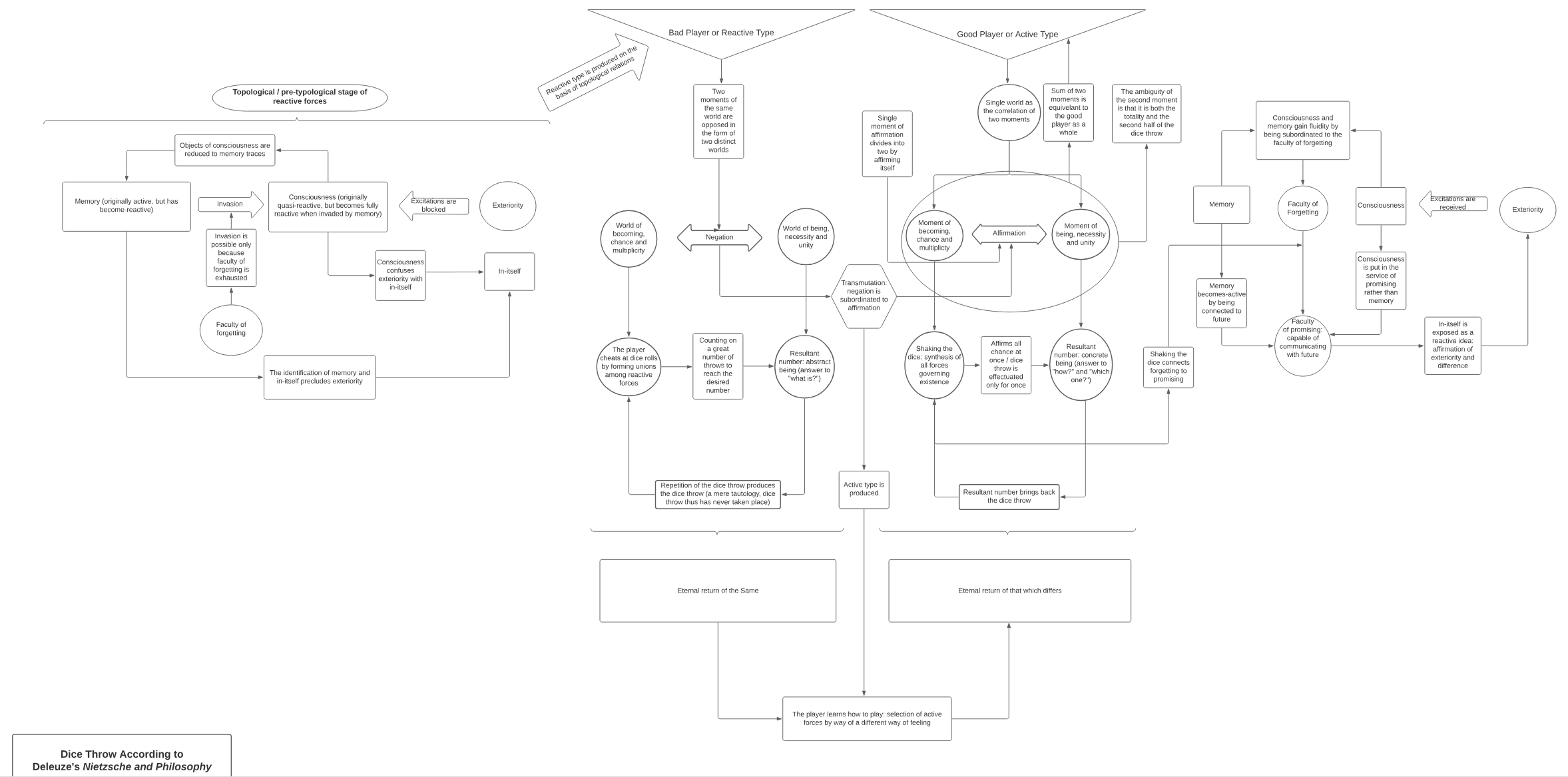

Law of Surprise, as Calanthe proclaims, is ‘a game’! A game with chance, a game with destiny!’ The underlying principle is interesting: the outcome is unpredictable, but, whatever the outcome, it is imperative and binding. Before fate is sealed, the outcome could be anything, pure chance, but afterward, it could not have been otherwise. It’s a game with destiny, after all.

By committing to play, the parties affirm whatever dice will come up, but they must also acknowledge that the outcome depends on others who are rolling their own dice simultaneously. These contracts, exchanges, oaths—they must be proven. The outcome is not predetermined, for destiny alone is not enough to forge reality. Something more is needed.

What is needed?

“Roegner knew the gravity of the oath he took. He took it because he knew law and custom have a power which protects such oaths, ensuring they are only fulfilled when the force of destiny confirms them. You have no right to the princess as yet. You will win her only when –’

“When what?”

“When the princess herself agrees to leave with you. […] It is the child’s, not the parent’s, consent which confirms the oath, which proves that the child was born under the shadow of destiny.”

– Geralt, A Question of Price

Choice.

Co-fatality.[1]

For people’s fates to become entangled, something more/additionally must be true. Destiny becomes true only when the people subjected to it consent or choose to affirm it.

Geralt wills a future, throws the dice.

The fairy tale is based on a dicethrow: l’affirmation du hasard—the ‘affirmation of fated chance’. As per Deleuze, ‘the dice which are thrown once are the affirmation of chance, the combination which they form on falling is the affirmation of necessity.’[2] And by necessity, we must say ‘Yes!’ no matter the outcome. Amor fati. Refusing to affirm the fated chance we have called into being—in whatever form it may present—can have destructive consequences. In the universe exist countless contested futures, and only mutual affirmation ties a thread of fate in the sea of chaos.

Ciri chooses Geralt. And Geralt, eventually, stops walking away from what he has called into being.

‘Geraaalt!’

He turned around. Ciri was standing on the brow of the hill, a tiny, grey figure with windblown, mousy hair.

‘Don’t go!’

She waved.

‘Don’t go!’

She yelled shrilly.

‘Don’t goooo!’

I have to, he thought. I have to, Ciri. Because… I always do.

‘You won’t get away!’ she cried. ‘Don’t go thinking that! You can’t run away! I’m your destiny, do you hear?’

That’s why they are connected by destiny.

There are many players gambling for one future or another. In Lady of the Lake, the Aen Elle enact the fairy tale, enforcing an analogous pact with Ciri. I say ‘analogous’, because the story has become considerably darker and complicated by now, concerning Ciri’s coming-of-age story wherein a girl should—by tradition—become a mother.

In return for something Ciri needs (return to Geralt and Yennefer), the elves wish to have her child. Even a ‘life debt’ has come into play against which the devil (or a wizard!) usually seeks something in return: by way of helping ‘Fate’ lead Ciri to the Tower of the Swallow, Avallac’h ensures no threat from the Continent can get to her again—ever. Even the spectres of the Wild Hunt appear on the ice at Tarn Mira in order to deter Leo Bonhart from catching the girl. Ciri slips through the Gate of Worlds and is ‘safe’ (at a price).

Arguably, Ciri owes her life to the Alder Folk in yet another way: her very existence as the Lady of Time and Space—a carrier of mutated Hen Ichaer, the blood of elves—has come about as a result of ‘a theft’.

‘We have the right to demand, and we can, O Swallow. Your father, Cregennan, took a child from us. You will give us one back. You will repay the debt. It seems just and logical to me.’

– Avallac’h, Lady of the Lake

The special child the elves seeks in redress for humanity’s theft is destined for great things, and due to the conditions under which the contract with Ciri is agreed upon, Ciri’s child will be born under the shadow of destiny in turn.

Interestingly, despite having several means for taking what they need by force, the Alder Folk pursue cooperation. Ciri’s consent in having the child is a big priority for the elves. Even Eredin makes mention of it: ’Not completely [prepared to co-operate]? Ha, that’s not good. Since the nature of the cooperation demands that it be complete. It’s simply not possible if it’s less than complete.’ As pertains to the near future, Avallac’h openly hopes that once she has given birth, Ciri will choose to stay with her child; with the elves and him.

‘We want to have your child, O Swallow, daughter of Lara Dorren. Only when you bear it will we permit you to leave here, to return to your world. The choice, naturally, is yours. What is your answer?’

‘My answer is no. Categorically and absolutely no. I don’t agree and that’s that.’

‘Tough luck. I admit I am disappointed. But why, it’s your choice.’

– Avallac’h, Lady of the Lake

Ciri’s affirmation in enabling her Fate is underscored repeatedly throughout the chapter. As Ciri, the Swallow, is already a Child of Destiny, her choices carry extra weight insofar as tying into the resolution of many people’s and worlds’ fate. Through her choices, destiny becomes manifest.

Naturally, there is a crux: such choices under duress can be considered blackmail.

‘The choice, as I said, belongs to you. You ought, however, to know something. It would be dishonest to conceal it from you. You can’t escape from here, O Swallow. So if you refuse to cooperate you will stay here forever, and will never see your friends or your world again.’

– Avallac’h, Lady of the Lake

The concept of Rumpelstiltskin-like fairy tales echoes blackmail because the favour the monster (or a wizard) extracts in return for his help is usually in some ways inconceivable or impossible to the party who has to fulfil it. The children the witchers take run a higher chance of dying horribly to mutations than becoming vaunted protectors of humanity. For Calanthe it was unthinkable to give up Pavetta to the Urcheon, or Ciri to the witcher after losing Pavetta. In turn, at Tir ná Lia, Ciri is not ready to become a mother in the first place, nor did she ask for Avallac’h’s help.

The original bind in the Witcher stipulates that choice affirms destiny, making it something more, something real. As Mousesack shows, the sword has two edges—neither the one who must pay nor the one demanding payment can escape once the bond forms.

‘How do you know Ciri would want to go with me? Because of some old prophecies?’

’No,’ Mousesack said gravely. ‘Because she only fell asleep after you cuddled her. Because she mutters your name and searches for your hand in her sleep.’[…]

‘You will not escape, Geralt.’

‘From destiny?’ The Witcher tightened the girth of the captured horse.

‘No,’ the druid said, looking at the sleeping child. ‘From her.’

– Mousesack, Sword of Destiny

Once a debt comes into fruition, the parties are linked with each other for better or worse. ‘Not choosing’ only delays the inevitable—destiny will keep reminding itself until fairness is served. And such fairness ultimately depends on how those bound together choose to treat each other.

In the light of this fairy tale, it is interesting that the wizard who exacts payment at Tir ná Lia sees red when Ciri—for the first time during her stay—actively offers it. To him.

‘Or you, perhaps?’ she yelled. ‘If you want I’ll give myself to you! Well? Won’t you sacrifice yourself? I mean, they say I’ve got Lara’s eyes!’

– Ciri, Lady of the Lake

Unlike Geralt who stumbled into the Law of Surprise, Avallac’h has meticulously engineered the circumstances of Ciri’s arrival. He has studied the bond between Geralt and Ciri, and he has been subject to an unhappy destiny himself—with Lara. He carries Elder Blood, like Ciri. What Auberon tries to teach Ciri, Crevan already knows: in every moment, infinite futures begin and countless pasts end as a result of our choices; choices, which, informed by our past and future hopes, shape how we interact with the present moment in which we take action.

‘The ancient Ouroboros reminds us that in every moment, in every instant, in every event, is hidden the past, the present and the future. Eternity is hidden in every moment. Every departure is at once a return, every farewell is a greeting, every return is a parting. Everything is simultaneously a beginning and an end.’

– Auberon, Lady of the Lake

In the end, this is how fate shapes up.

Avallac’h believes in Ithlinne’s Prophecy and prophesizes himself, but also acts in ways that steer the workings of Fate (as does Geralt, in a minor way, by calling the Law of Surprise; acting as Ciri asserts one must do: ’You can’t just sit and do nothing! Nothing comes by itself!’). Arguably, he understands destiny’s rules—powerful bonds form when people choose and consent to its pull. For destiny to manifest, you must actively pursue it. Moreover, Crevan already considers Ciri’s fate as bound to his, telling Geralt point-blank under Mount Gorgon—after a small, thoughtful or anxious, hesitation— ’someone else will help her now. You can’t be so arrogant as to think that the girl’s destiny is exclusively bound to you.’

Now though, irony strikes.

By offering herself to him—to bind her fate to his—Ciri makes an unexpected dice throw. Alongside a jab about Lara’s eyes, which must surely make the matter of destiny obvious. Now the wizard, who has not come to grips with his fate (and trauma)—analogously to the witcher in Brokilon—faces the Child of Destiny declaring that Ciri—not Lara—will give herself to him, will consent to bringing about a fate the woman Avallac’h loved (and can’t let go) did not choose to affirm. It becomes a moment of supreme irony when Ciri—a twist of Fate—straightforwardly tells the wizard she chooses him to do what Avallac'h was once meant to do with a different woman, whose debt and eyes she bears.

Ciri never actively chooses Auberon. She goes along, circumstances being what they are, but it does not work with him for the same reason it does not work with Emhyr—Ciri reminds the Alder King of his daughter. He continues walking away from her every time Ciri might possibly come to believe ‘choosing’ him is an option; that she herself could be chosen. Indeed, as destiny from which we walk away can manifest in different ways, Ciri eventually closes the circle for Auberon—as Death. As things do not pan out, Ciri acts (for you can’t just sit and do nothing): it’s clearly not working with Auberon, thus it’s clearly not my destiny to have this child with him; but I want to fulfil the contract, and I’ll choose you if you want—what do you say?

In its frustration and desperation, Ciri’s offer to Avallac’h comes off as a perversion of the way Ciri first chooses Geralt.

Standing on a hill, Ciri informs Geralt that he cannot escape. Now she does it again, unconsciously.

‘What you wanted and what you planned to do ceased to matter [from the moment Ciri was born], and what you don’t want and what you mean to give up doesn’t make any difference either. You don’t bloody matter!’

– Mousesack, Sword of Destiny

Avallac’h wanted Lara, planned to have a child with Lara, and was likely willing to give anything for Auberon’s daughter not to make the decisions she made. It did not make a difference. Now, he envisions the Swallow having a child with Auberon, staying with the child, with himself as an orchestrator/guardian, not a direct participant—it does not make a difference. The alternative is himself and his laboratory. Except the alternative spooks the devil (or a wizard) who demands payment for a debt.

‘In accordance with the Law of Surprise and eternal custom, the decision is yours. Answer. One word from you is enough. Yes, and you become the property, the conquest, of this monster.

No, and you will never have to see him again.’

– Calanthe, A Question of Price

The monster might as well be Ciri in this scenario. It’s deepest irony and destiny’s dark sense of humour to give Avallac’h exactly what he wanted, but in a form he cannot—at least at this point in time—accept. Rather than seeing a new possibility for fate to manifest, he reacts from his trauma. He is not ready; he has not processed his past and has not moved beyond idealized versions of how things ‘should be’; and he is using control as a defence mechanism against abandonment. Ciri’s offer—despite offering to close the circle of Lara’s rejection with acceptance—triggers these unresolved issues. Moreover, Ciri is not in any position yet to resolve her own traumas, nor define herself in relation to her elven heritage, nor to become a mother. Moreover-moreover, before a new chapter in Ciri’s life could begin, as this is her coming-of-age tale, she must wrap up the previous one. As in Brokilon, the time (and context) for dealing with the way these dice fell is just not right.

Avallac’h in the books is not yet able to truly accept necessity, despite affirming chance. Running, he repeats Geralt’s early mistake. By rejecting her offer, he paradoxically repeats both Lara's rejection of him and his own rejection of her choice. He, who forges destinies, cannot bring himself to embrace destiny manifesting in unexpected ways, and it prevents him from seeing how Ciri’s offer—even if born of frustration—could fulfil the greater pattern of elven fate he claims to serve.

For now.

Footnotes

When multiple dice are thrown together (people’s desires for a particular kind of future), each individual die’s result is contingent, but they form a single throw whose components are now bound together—they become ‘co-fated’. The results couldn’t have been different without the entire throw being different. Or: it’s not sufficient for a man to see himself and another as lovers, since the other person must consent to loving him. ↩︎

Deleuze, G. Nietzsche and Philosophy, p. 26 ↩︎