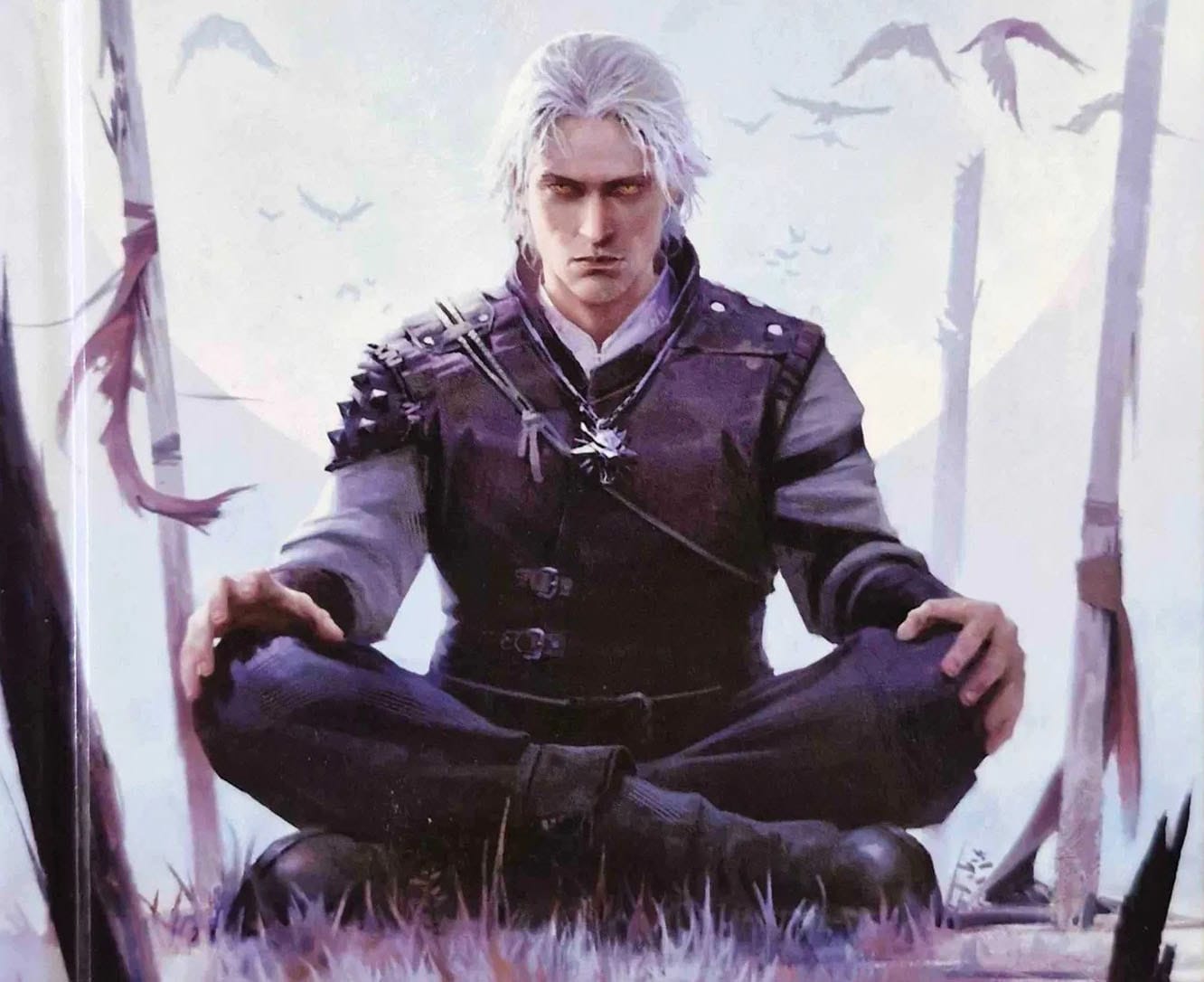

Analysing Rozdroże Kruków | Crossroad of Ravens–Andrzej Sapkowski's Latest Witcher Novel

We live (on) in our successors. In them, our sins live on too. Geralt learns his profession and internalizes witchers’ generational trauma. Witchers have absent mothers and distant fathers who'd love to vivisect them. His quest for vengeance abates when he reaches the sea.

Critical decisions are made at the crossroads. To dive anew into the well-trodden bygones or to let history’s weight pass through you gently, as you set eyes upon new horizons. While promising more Witcher stories to come, Rozdroże Kruków sees Andrzej Sapkowski drawing one particular thread of his saga into sharp relief—as if holding it up to the light for his readers, old and new, to see more clearly.

If this book instead of Wiedźmin had been the opening salvo to a fantasy cycle, however, I would have moved on fast. As a standalone, too, it’s run-of-the-mill. But young adult journeys are full of aborted false starts. And for what it actually is—a prequel character piece—it’s inoffensive, light reading; chock full of narrative rhyming and nostalgia bait. Sapkowski does not surprise nor excite, serving up a home cooked comfort meal; familiar, though forgettable. Character work, as ever, holds the dish together.

There is some mystique decay and a lot of recycling; retroactive strengthening of parallels. Most of it is inoffensive (the origins of Płotka, Geralt’s bandana, swords, attraction toward older women, aversion toward killing nearly-extinct creatures) if eye-rolly, but the narrative echo binding young Geralt to as-of-yet unborn Ciri insists upon itself too much.

‘Listen to what?’ shouted the Witcher, before his voice suddenly faltered. ‘I can’t leave—I can’t just leave her to her fate. She’s completely alone… She cannot be left alone, Dandelion. You’ll never understand that. No one will ever understand that, but I know. If she remains alone, the same thing will happen to her as once happened to me… You’ll never understand that…’

– A. Sapkowski, Time of Contempt

The emotional impact of this fragment in the saga does not increase as a result of Crossroad of Ravens. It is not strictly necessary for both Ciri and Geralt to come close to dying on the eve of the Equinox, receive facial scars, and, for a while, walk the same path—dealing out retribution. The repetition could have come with a twist to mask its repetitiveness. Oh, well. Fortunately, the point the original saga makes stands solid without further ados.

Some of the lore is still genuinely interesting for fans (the sacking of Kaer Morhen, relations between sorcerers and witchers, Kaedweni political geography), even if they will have to sit through the deployment of fencing dictionaries for it. The chef’s been on leave, but all the ingredients are still there: the in-universe apocrypha, sardonic wit, bloody rituals, women’s and witchers’ rights, and blooming apple trees. Alas, it lacks something more.

The book feels like an overt advertisement for one particular ostinato of The Witcher Cycle: the weight we pass on. Inside the witchers’ trauma we can recognise the experiences of women—bodies violated and remade by the powerful, the constant tension between utility and revulsion. Inside Geralt’s story of leaving home for the first time hides Ciri’s tale of first losing hers… Or did the ideas not occur the other way around? Crossroad suffers from the thoroughness with which the author has already handled certain themes; it treads worn ground, failing to reach the sea and new horizons. Although, perhaps, preparing ground in this way among new audiences and really driving in a point before Ciri will start engaging with the weight of her own legacies in CD Projekt Red’s new trilogy.

Geralt as a Young Man

Do not remember the sins of my youth nor my transgressions.

– Psalm 25:7

Young Geralt sets off from Kaer Morhen the day before the Equinox and one life—of youthful maximalism—begins, until, on the eve of another Equinox, he almost dies, and life as he conceives of it in this book ends.

Geralt, the wunderkind, is a callow, naive boy with a heart of gold and a pocket book of Rules and Regulations the world only pretends to give two shits about. He tosses a coin, should a beggar catch his eye. He doesn’t accept payment when he comes across someone in trouble. He lectures bigwigs on legal permission to practice his craft, and he interferes—all the time. Until a blacksmith reminds him that everyone should mind their own business. His first monster is a rapist? Too bad. Geralt is forgetting an evergreen rule: killing men brings murder charges, killing those whom men hate today brings accolades. Pronouncing guilt lies outside of a witcher’s competence. Justice is not a witcher’s business. Hence our wunderkind’s well-known agony: he is not a perfect, emotionless witcher, he is a defect requiring repair.[1]

Barely legal and precocious, Geralt wishes to see the world, but almost gets hanged in his backyard by trying to save people from people. Endearingly serious, he is frequently frustrated at his own inexperience and ignorance. Geralt—just Geralt—does not know what big words mean, but sighs after a few prefixes to mask his own backwoods upbringing. Geralt Roger Eric du Haute-Bellegarde, as we know, is the brief outcome.[2] There’s purple poetry in his step on account of the fantasised heroism of his profession. But the populace quickly sets to disabusing their newest pest controller of such notions. Never having moved among people, Geralt gets his first taste of isolation: he does not feel good in crowds; he gets overstimulated. He is unready—mentally and physically—for the lonely existence that dogs a witcher for the sin of his nature.

Fortunately, experienced company finds him during that first aborted foray into his profession; albeit not without an ulterior motive. In choosing to work per procura of Preston Holt, Geralt binds himself for a while longer to Kaedwen, to Holt, the Temple of Melitele in Elsborg, and to the shadow of the sack of Kaer Morhen. He clings to the geography of his childhood. Learning to kill bare-handed—for what virtue is there in accepting abuse?—and to do business. Learning to cast down his eyes before sorceresses, who, in his mentor’s experience, treat regular people as cattle and despise witchers in particular. A witcher’s skin is a chronicler. Geralt learns his profession as an extension of Holt and thus, internalizes witchers’ generational trauma.

Wizards, Witches, and Witchers

“The first witchers were children of women with uncontrolled magical abilities, called witches. They were insane and often served as sexual toys to horny young men. Children, the results of such games, were abandoned. ... All of us, witchers, descend from intellectually challenged girls.”

– Preston Holt, Crossroad of Ravens

Demand for witchers originated in the military-industrial complex. An elite Circle of Wizards decided to meet the demand for superhumans. Their methods differed—corpses, foetuses in the wombs of their mothers, tiny children—and the laboratory crematoria smoked continuously and for a long time. The result was supposed to constitute a new step on the evolutionary ladder of humanity; an improved version of the human species. An emotionless killer—a transitional form from which, through natural selection, a new, better human race would eventually emerge.

Once the mutagen, anatoxin, hormone and virus had been created, one of the wizards stole the material and fled. Allegedly, for the common good. The rationale? The transhuman ought not to remain in the power of Lords and Sorcerers alone, but should be put into the service of the general public; protecting and saving people from monsters. In Mirabel, in the North, beyond the Toina river, first witchers were created, after which Beann Grudd and Kaer Morhen were established. The renegade wizard had by that point already met his end. But the gears were turning, the product diversifying.

It's not coincidental that witchers rank in many ways the same, if not lower, than women in the society they are supposed to save. Both are often unable to defend themselves without incurring worse retribution from those in power. Both are bodies to be used: women for breeding, witchers for killing; both subject to violation in the name of progress or pleasure. They are objects of the ambitions, desires, and fears of the powerful. Common folk believe witchers are assembled from various human fragments, sewn, or glued together, automatons birthed by village witches but constructed by sorcerers. A witcher's touch, as Geralt fast learns, carries a stigma: many brothels refuse to serve them publicly, as other clients might not want a girl who has been touched by a mutant. Yet their bodily fluids are of great interest to the class that created them; a class that controls and influences the social mores and prejudices affecting them. Sorceresses and sorcerers are the powerful of this world; transhuman already. Their shadow selves—village witches, whose mind breaks under Power, and witchers, who are hammered into shape with it—serve as experimental material. They must function as intended, yield what is required, or be discarded.

Witchers have absent mothers and distant fathers who'd love to vivisect them, mirroring the society that created them: born of the marginalized, shaped by the powerful, yet trusted by neither. Despite their abilities, they are viewed as deficient. Less than Man. In society's eyes, a witcher's “birth” necessitates he labour all his life to make even; kill things that try to eat man in order to negate his original sin of having been created as something more than man. Geralt is one of the last to set out on the trail from Kaer Morhen, but he does not believe himself to be a successful specimen. A witcher with scruples is unreliable. But is Geralt an aberration, or the new, better man—wielding inhuman power not at the behest of lords and sorcerers, but according to his own conscience?

Vigilantes vs Defenders

“When nature encounters a mutation, it fights it. You have no choice, young witcher. You must accept your own imperfection.”

– Preston Holt, Crossroad of Ravens

"There is a time to be born, and a time to die;

a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted;

a time to kill, and a time to heal."

– Ecclesiastes 3;2

Rocamora.

Roac a moreah.

In the Elder Speech: revenge.

We live (on) in our successors. In them, our sins live on too.

When Preston Holt saves an unseasoned witcher from being hanged, it’s with the intention of gaining himself a healthy, young executor of his will in his unfinished quest for justice. The white-haired Geralt even looks like Holt—his spectre. A successor to his work. But what work! Returning evil deeds in kind: avenging the Kaer Morhen witchers, massacred in collective punishment for a kill that may or may not have been committed in self-defence by a colleague. Then Holt changes his mind.

Preston Holt becomes for Geralt as Geralt is to Ciri from the start: a mentor who would like to save you from walking the path they have already walked, and ruining yourself—after having put you on that path, that is.[3] In wishing to honour and secure our legacy, we plant the weight comprising it. The sins of Preston Holt’s youth saw him run when the mob attacked Kaer Morhen. He has been making up for his cowardice ever since. He has built an altar to his quest of his very home, and, despite growing hardships, refuses to move on. There would be no punishment for scoundrels, unless someone made it.

An imperfect witcher gets emotionally invested.

It’s fairly clear with Crossroad that there is no uniform outcome to Trial of the Grasses. As Holt tells Geralt, mutations can mutate spontaneously. Errors are inevitable. In spite of being more experienced, Holt turns out to be “flawed” similarly to Geralt. But Geralt fails as a witcher precisely where he succeeds as a human—by caring. And so does Holt.

“I,” Holt continued, “unlike you, knew what I was doing, and I was aware of the consequences. I acted according to a plan. That plan did not include your pathetic, senseless, and purposeless intervention.”

“I wanted to save you...”

“And I wanted to save you,” Holt snapped back.

When is revenge no longer worth it? When something else begins to matter more in its place.

Geralt’s quest for vengeance abates when he reaches the sea. A foreign, new horizon. The moment of choice arrives to the cawing of a raven in the top of a tall tree: before him, his quarry scrambles to escape; yonder, a monstrous centipede crawling toward playing children on the beach. And the young witcher, for once, heeds the raven. He stops looking backward, meeting evil with evil. Instead of continuing to pay back for past wrongs, he chooses to prevent future harm. He performs an act of good; and may it return in kind.

Footnotes

In Wiedźmin, Geralt saves the strzyga. He dances with the cursed creature until dawn and breaks the curse. At 18, he botches the job. Overcome with fear at the difficulty of his task, he fails at making a Sign and panics. Result: a very dead, very headless strzyga. ↩︎

It’s an interesting contrast with Ciri, who goes by her nickname as often as she can, escaping in this way from her legacy as Cirilla Fiona Elen Riannon. A noblewoman, and much more besides. ↩︎

“But it turns out that fate cannot be cheated.” Despite saving Ciri’s life and trying to prepare her as best he could for the world, Geralt cannot help but labour under a massive burden of guilt throughout the Saga. As any parent, who takes responsibility for the path they introduce their dependant to. ↩︎